An Analysis of Language Ideologies in Disney’s “Moana”

University of California, Irvine, 2017. Linguistic Anthropology.

[Assignment prompt: Analyze language ideologies in a popular animated film released after 1994 and intended primarily for children. Reference Rosina Lippi-Green’s article “Teaching children how to discriminate,” in English with an Accent, 79-103. London and New York: Routledge, 1997.]

“A smooth sea never made a skilled sailor”

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

a

Inspired by the remarkable voyaging heritage of early Polynesians and their mythology – particularly the shapeshifting, trickster demigod, Maui – Disney creatives, led by Ron Clements and John Musker, and a team of Pacific Island experts, worked for 5 years to craft Disney’s 2016 film Moana (Robinson 2016). Not only does Moana include Disney staples – an imaginative adventure, compelling characters, memorable songs, and vibrant, state-of-the-art animation – it is also Disney’s most successful portrayal of a nonwhite culture. Set in a fictional Polynesian village two millennia ago, on the brink of a new wave of major Polynesian exploration, the team incorporated a fusion of Polynesian cultural traditions to create Moana’s world (McEvers 2016). Authenticity extended to casting: all leads and most of the cast are of Polynesian descent (Rhoades 2016). Moana was a critical and box office success, receiving praise worldwide as a tribute to Polynesian culture. It was well received by the people whose cultures it depicts, despite several criticisms, the most widespread concerning Maui’s representation (Wikipedia 2017). [Note 1]

In ancient times, the brash-but-likeable demigod Maui stole the heart of Te Fiti – believed to hold the power of creation – to earn favor with the humans whose love he craved. Before he could deliver the heart, he was struck down by Te Kā, a fearsome lava monster, and a blight began to spread throughout the region, stoppable only by restoring Te Fiti’s heart. Maui’s legend was passed down by storytellers like Gramma Tala – spirited mother of the village chief, and supportive grandmother of our courageous protagonist, Moana. Moana’s name means “ocean” (Il Post 2015) [Note 2], and all her life, she’s felt its pull, despite her parents’ attempts to keep her safe and focused on her responsibilities as future chief. Only Gramma Tala encourages Moana’s adventurous spirit and shows her the truth of her ancestors: they were voyagers. When destruction threatens her village, Moana trusts her inner guidance and embarks on a journey to save her island by restoring Te Fiti’s heart. She seeks out Maui, who helps her defeat several adversaries – including Tamatoa, the enormous, narcissistic crab, who has acquired Maui’s magical hook. They work together to restore the heart, revitalizing the lush abundance of the islands and reopening the world to Moana’s people, as Moana teaches them the wayfinding and voyaging of their ancestors. Moana and Maui learn from each other and grow in awareness of who they are and what matters to them.

This paper explores the characterizations of Moana, Gramma Tala, and Tamatoa, referencing findings in “Teaching children how to discriminate” by Rosina Lippi-Green (1997. Herein LG).

Moana’s characters feature varied body types, historically appropriate costumes, and intricate tattoos. Interestingly, Moana and her mother, who most embody LG’s sense of “attractive” females, have either no tattoos or very discreet ones, respectively. As this is not necessarily typical (Losch 2003), it may reflect Disney’s conservative preferences. While drawn with more realistic proportions, Moana and other “desirable” female villagers could be characterized as incarnations of LG’s “doe-eyed heroines with tiny waists” (LG 1997:95).

Ancestral characters sing exclusively in Samoan and Tokelauan (Tauafiafi 2015), reminding us that Moana’s characters would not logically speak the Standard English (SE) used in nearly all dialogue – peppered with varied accents and some non-Anglicized pronunciations of proper nouns (e.g., fewer diphthongs and a dental “t” as in [t̪e `fi: t̪i] rather than [teɪ ˈfidi]). Only six characters have more than two lines, and most actors speak with their native accents (referencing interviews and biographies; IMDb 2017). Mainstream US English (MUSE) speakers include protagonists Moana and Maui, and Moana’s mother, with Maui occasionally using US slang/casual expressions (“bod,” “breakaway,” “Maui-out”). Moana’s father and Tamatoa speak New Zealand English (NZE), which, though potentially unfamiliar to some, may be associated with a British, rather than “foreign” accent (defined as that of a non-native English speaker). Gramma Tala is the only principle character who speaks SE with a foreign accent. All accents but hers reflect the presence of later colonial powers.

Rachel House (native NZE) affects a gentle accent that could have descended from a native Polynesian language. She tends to use approximately [d̪] and [t̪] sounds, and her final [r]s are not pronounced (e.g., ear [i:jə], restore [rI ‘stoʊ: ə , heart [hɒ:t]. Tala’s voice is honeyed: very low, softly raspy; without visual or contextual cues, I may have presumed African. She is the only female character with any kind of accent other than US and the only speaking female who stands out as an “other” in appearance and behavior. Tala is the self-proclaimed “village crazy lady.” Though she is active, her body is larger than the other women’s and she bears a prominent tattoo of a manta ray on her back. She is respected and wise, if eccentric – the keeper of ancient stories and secrets. She often separates from the group – to dance along the beach while others engage in village activities – and is frequently joined by Moana. Tala is Moana’s greatest supporter in life and death; she is reincarnated as a ray like her tattoo and becomes Moana’s spirit guide, encouraging her throughout her voyage and appearing in spirit form when Moana must decide whether to persist or resign her quest. Gramma Tala’s unique accent emphasizes her connection to ancestral ways, as do her mystical expressions and phrasings (within SE boundaries) – most obvious in her storytelling and the way she guides Moana:

- “You may hear a voice inside … Moana, that voice inside is who you are.”

- (showing, rather than directly telling Moana) “The answer to the question you keep asking yourself: who are you meant to be? Go inside, bang the drum, and find out.”

- “The ocean chose you.”

Tala’s most memorable guidance is this ‘mission statement’ (lines 8-9), which Moana frequently repeats, with varying delivery and for differing purposes: as an introduction, an assertion of power, and a way of encouraging herself by affirming her purpose. [Note 3]

(1) Gramma Tala, dying, in a belabored whisper; building strength until the final line:

1 Tala: h < weakly > Go. h

2 Moana: < fear > Gramma?

3 Tala: (.) h Go. h

4 Moana: Not-h now. h I h?can’t.

5 Tala: You ^must. The ocean chose you. Follow the fishhook. /

6 Moana: / Gramma.

7 Tala: / h And when you find Maui, h: you grab him by the ear.: You say: h: < stronger >

8 I am Moana: of Motunui.: You will board my boat, h: sail across the sea, h: and

9 restore the heart of Te Fiti. h:

10 Moana: I…h I can’t leave you.

11 Tala: There is nowhere you could go that I won’ be with you.

12 (n.n) Go.

Moana is a beautiful and active 16-year-old, the future leader of her village – though she emphasizes that she is not a “princess.” She loves her family, is involved in her village, and takes her responsibilities seriously – but often sneaks away to pursue her own interests. She struggles with whom and what she is meant to be. Unlike most Disney princess-figures, Moana has no love interest. She cares for pets Pua and Heihei; neither speaks nor is treated as an animal-sidekick conversation partner as in other Disney films.[Note 4] Moana acts out of a sense of love, devotion, and a need to be true to herself. Moana’s character was developed before casting Auli’i Cravalho, Hawaiian native and industry newcomer who, at age 14, became Disney’s youngest voice of a princess-figure (Jost 2016). Moana speaks neutral MUSE; her vocal timbre and expressions sound surprisingly similar to other recent Disney princesses: young, lively, and with a clear, pleasing tone. She and Maui banter and tease in ways familiar to American audiences, and Moana often sounds like a typical, middle-class American teenager – believing her father forbids her to sail because he “doesn’t get [her],” using expressions like “what is your problem?!” and occasional ‘girly’ laughter and vocalizations. Some of these features appear in this excerpt, as the Kakamora horde attempt to seize the heart:

(2) Heihei has swallowed the heart and is captured by the Kakamora. Throughout, Moana lets out several (low to high to low intonation) “Uh!”s and other high-pitched squeals to express frustration.

13 Moana: < high pitched yelling, frustrated > Maui.! They took the heart!

14 Maui: < coolly, condescendingly > (.) That’s a chicken.

15 Moana: < same tone as above > The heart is in the … < girly squeal of frustration >

16 We hafta get ‘im back. (.)

17 < yelled, extreme high-low pitch variation > Maui!

18 Maui: < seems to pursue Heihei; instead, jumps off boat, yelling > ^Chee-hoo!.

19 Moana: < thrown off balance from Maui’s jump. Low pitch to high squeal > Wah?

Moana’s language is slightly modified when assuming leadership duties, perhaps reflecting the language ideology that leadership demands a confident and more formal delivery, with a tonal pattern similar to the “Standard American Melody” (Thorpe 2014). Her delivery in this excerpt expresses both uncertainty and confidence in problem solving. Her choice of “will” indicates a more formal register than when she has less confidence in her solutions or converses with intimates.

(3) Villagers bearing rotten coconuts approach leaders:

20 Female: < with regret/concern > ^It’s the harvest. This morning,: I was husking the coconuts

21 ^ and ^ … (n.n) < shows rotten coconut. Others also approach. Looks of concern. >

22 Moana: ^Well… We should clear the diseased trees. ^And (.) we will start: a new grove, uh:

23 there.

Toward the end of the film, when addressing Te Kā/Te Fiti, Moana assumes a reverent tone and somewhat mystical phrasing, like Gramma Tala:

- “I have crossed the horizon to find you. I know your name. They have stolen the heart from inside you, but this does not define you. This is not who you are. You know who you are. Who you truly are.” (Moana places heart in Te Kā; blackness crumbles, green growth spreads – revealing Te Fiti).

LG mentions casting based on celebrity persona association (particularly as a shortcut to characterization), and two such cases may be present here: Maui and Tamatoa. Though Jemaine Clement may not be as widely known as “The Rock,” his absurdist comedy fits perfectly with Tamatoa’s unusual brand of villainy. One of three antagonists, Tamatoa is the only ‘bad guy’ or animal who speaks – and though his Kiwi accent is similar to that of Moana’s father and other villagers, his character traits and musical styling (his is the only song that does not have Polynesian influence) accentuate the chasm between Tamatoa in his monstrous lair and the villagers. Not a typical villain, Tamatoa does not actively pursue a nefarious scheme, but will eagerly prowl on convenient offerings (including Moana and Maui). Tamatoa is the only character who wounds with words – exploiting Maui’s insecurities and longings – and sole proponent of the “looks are what’s important” ideology (weakened by its association with a villain). His primary interest is accumulating treasure to decorate his vast shell, which is crowned by Maui’s fishhook. After Maui and Moana outwit him, he is left stranded on his back, unable to right himself. This enormous crab is greedy, vain, and changeable – shifting abruptly from ‘menacing adversary’ (evil laugh, commanding delivery in deep, gravelly tones, intelligent, precise vocabulary) to ‘comedic animal sidekick’ (faster, casual speech, higher tones, and a clearer voice). This unpredictability does not establish him as someone we identify with and want to be like.

(4) Upon discovering Moana:

24 Tamatoa: < serious, mid-range pitches > What are you? doing down here: in the realm:

25 < slower, deep tones, foreboding > of the monst-: < lighter, friendlier, faster >

26 Just pick an eye, babe. I can’t- I can’t concentrate on what I’m saying if you keep-

27 Yep, pick one. < demanding > Pick one!

(5) This vocal and intentional variation is typical for Tamatoa:

28 Tamatoa: < menacing, slow, very low, gravelly pitches > Are you just trying to get me to

29 talk about myself?: < threatening > Because if you are. (.)

30 < friendly, pleased, bright, clear tone > I will gladly do so! In ^song form!

He narrates his thoughts, explains events, and acknowledges the audience:

- “Oh, I see, she’s taken a barnacle and she’s covered it in bioluminescent algae…as a diversion.”

- (To Maui) “What a terrible performance! Get the hook?! (next, to camera) “Get it?”

- (After credits, still flipped on his back. He petitions the audience) “Can we be real? If my name were Sebastian <Little Mermaid> and I had a cool Jamaican accent, you’d totally help me.”

Moana breaks some of the ideological stereotypes outlined by LG while perpetuating others:

- Lovers: Though not “lovers,” Moana and Maui conform to typical protagonist expectations. Ideology: a cool/desirable hero must speak MUSE (and females must fit Western beauty ideals).

- Parents: Moana’s mother speaks MUSE and her father, NZE. Ideology: parents speak mainstream forms of English. Moana is one of the few Disney heroines whose parents survive the entire film.

- Outsiders: Human “otherness” is somewhat diminished in Moana. Unlike spirit guides Rafiki and Mama Odie, Gramma Tala is much more similar to and included in her community. She speaks with a foreign accent, but it is gentle, and though her expressions have a mystical air, they are expressed in SE. Tamatoa is also less isolated by his Kiwi accent (shared by other “good guys”) than by his erratic (but laughable) behavior and values. His reference to Sebastian’s “cool Jamaican accent,” indicates popular approval and encourages us to agree with that inclusive ideology.

- Motivations and choices: Ideology: “Good guys” get happy endings. All females and all human males act from pure intentions. Maui, a male MUSE speaker develops from flawed to good.

- The most interesting LG stereotype Moana breaks is that females’ alignments do not change. In the movie’s biggest twist, Te Fiti, giver of life, and Te Kā, raging lava monster, are revealed to be the same character – the first instance of a female character progressing from good to bad (unknown until the end) and bad to good (when her heart is restored).

Characters we identify with continue to speak SE; heroines are beautiful, lithe, and young; non-conformers may be lovable, but are peripheral; and some choices are not available to all – but Moana also progresses in the inclusiveness begun in the ‘90s byrespectfully and nobly portraying Polynesians and creating a relatable “princess” for all.

My friend Maddie, age 12, who loves Moana,says, “I think the meaning of the movie … is to never doubt or underestimate yourself and your abilities. The ocean chose Moana and she knew she had to go beyond the reef. Moana’s parents told her she can’t, but on the other hand her grandmother believed in her! She tried and succeeded after the second try! Nothing is impossible!!” Friends with young children commented how much their kids like the music. Moana’s solo “How Far I’ll Go” addresses questions of identity, determining what is right for you, whether to trust your heart – and I can only imagine positive results for children who grow up repeatedly singing those messages, compared to ideas expressed in many (beautiful and memorable) earlier songs.

Moana continues the shift in recent Disney movies to present strong, courageous heroines (sometimes without a love interest) who take active roles in their stories, aided by Disney’s signature touch of magic, and preserving classic values of kindness and integrity. “Empowered” heroines seem to have more choices in how they spend their lives – no longer restricted to caring for the home or waiting for a prince. Their stories and feats are so fantastic, their inner longings so strong and specific that I wonder whether this puts pressure on children – especially females. Must heroines save (and/or rule) their kingdom or region from disaster, have magical powers, or be the most beautiful – must they have a special quest and daring mission in life – to fulfill their destiny? To be worthy? Everyone likes an exciting story enacted by dazzling characters – but in the future, I’d like to see admirable heroines who also have the choice to just be ‘ordinary.’

.

Bibliography

.

Bucholtz, Mary. “‘Why be normal?’: Language and identity practices in a community of nerd girls.” Language in Society 28 (1999): 203–23.

Clements, Ron and Musker, John, dir. Hall, Don and Williams, Chris, co-dir. 2016. Moana. Burbank: Walt Disney Pictures, Inc. DVD.

Il Post, Cultura. 2015. “In Italia il nuovo film Disney si intitolerà ‘Oceania’ e non ‘Moana.’” Il Post website, Dec. 3. Accessed Jul. 24, 2017.

IMDb. “Moana (2016).” Accessed Jul. 24, 2017.

Jost, Elise. 2016. “The Ocean Is Calling: 7 Things You Might Not Know About Disney’s ‘Moana.’” Movie Pilot website, Nov. 28. Accessed Jul. 24, 2017.

Lippi-Green, Rosina. “Teaching children how to discriminate.” In English with an Accent, 79-103. London and New York: Routledge, 1997.

Losch, Kealalokahi. 2003. “Role of Tattoo.” PBS website. Accessed Jul. 25, 2017.

McEvers, Kelly. 2016. “’Moana’ Actress Grew Up With The Polynesian Myth That Inspired The Movie.” NPR website, Nov. 23. Accessed Jul. 24, 2017.

Rhoades, Shirrel. 2016. “Disney’s ‘Moana’ avoids whitewashing with Polynesian cast.” Rocky Mount Telegram website, Nov. 24. Accessed Jul. 25, 2017.

Robinson, Joanna. 2016. “How Pacific Islanders Helped Disney’s Moana Find Its Way.” Vanity Fair website, Nov. 16. Accessed Jul. 24, 2017.

Tauafiafi, Lealaiauloto Aigaletaulealea F. 2015. “Tokelau Pride: Te Vaka’s song for Disney’s Princess Moana.” Government of Tokelau website, Aug. 24. Accessed Jul. 24, 2017.

Thorpe, David. 2014. Do I Sound Gay?. New York: Sundance Selects. Netflix.

Wikipedia. “Moana (2016 film).” Accessed Jul. 24, 2017.

.

Notes

.

[1] Doug Herman, Hawaiian and Pacific Island cultures specialist, offers an insightful critique of the cultural and historical efforts of the film. Despite its shortcomings, he generally views the film positively – especially in its ability to widely disperse the incredible feats of the early Polynesian voyagers with an inspiring story and admirable heroine.

[2] This source also discusses Moana’s renaming as “Vaiana” (“water that flows from a cave”) in some markets (including the French Polynesian and New Zealand English releases). Based on my visit to French Polynesia and New Zealand in April 2017, I presume the name change in those areas may have been due to “Moana” being used frequently in ordinary speech/settings, and seeming less like a proper – especially memorable heroine’s – name. I have not been able to find any relevant documentation about the name change in Polynesian markets, or the reason “Moana” was retained in the US and others.

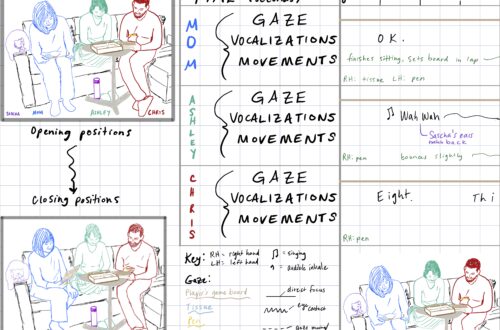

[3] Transcription methods, verbatim (Bucholtz 1999:221-222):

. end of intonation unit; falling intonation

, end of intonation unit; fall-rise intonation

? end of intonation unit; rising intonation

– self-interruption

: length

underline emphatic stress or increased amplitude

(.) pause of 0.5 seconds or less

(n.n) pause of greater than 0.5 seconds, measured by a stopwatch

h exhalation (e.g. laughter, sigh); each token marks one pulse

( ) uncertain transcription

< > transcriber comment; nonvocal noise

{ } stretch of talk over which a transcriber comment applies

[ ] overlap beginning and end

/ latching (no pause between speaker turns)

= no pause between intonation units

Additionally:

… speaker does not finish thought/trails off

^ rising intonation

[4] This piqued my curiosity as to whether this portrayal was simply a convenient movie choice or something recommended by Disney’s Polynesian advisors. I drew a parallel between the treatment of animals depicted in Moana as pets and that of pre-crawling Samoan babies, especially in light of the findings presented by Ochs and Schieffelin in “Language Acquisition and Socialization: Three Developmental Stories and Their Implications” (p. 309, Linguistic Anthropology: A Reader, Second Edition [Edited by Alessandro Duranti]).